How to repair old brickwork

Learn how to spot brickwork problems with a simple maintenance check, and how to repair damage to avoid potential structural issues

Get small space home decor ideas, celeb inspiration, DIY tips and more, straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Original brickwork is worth cherishing. During the Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian eras, millions of bricks were produced and used in many different styles, enriching the diversity of our architectural heritage.

If you are renovating an old house, or simply carrying out some seasonal maintenance, a basic understanding of brickwork will help you get underneath a property’s skin and assess any repairs that are needed.

Ivy and other climbing plants might add character to a house but, over time, they will damage the brickwork

Do I need to maintain my brickwork?

Although apparently durable and solid, brickwork tends to fail if mistreated. Repairs made using inappropriate cement mortars, poorly maintained rainwater goods that result in water spilling down the face of the wall, and coatings of ‘plastic’ paints and sealants are frequently the cause of damage to bricks.

more from period living

Period Living is the UK's best-selling period homes magazine. Get inspiration, ideas and advice straight to your door every month with a subscription.

Cracking and other problems may also result from movement in the structure of the building itself.

Until around 1919, brick walls were generally solid and built using weak and permeable mortars, plasters and renders based on lime, or sometimes earth or clay. While these materials absorb moisture, they also allow for easy evaporation.

The water vapour is dispersed externally due to the drying effect of the wind and the sun, and internally as the result of draughts entering via gaps in the building’s fabric and the traditional use of large open fires that draw air through.

Providing buildings constructed in this way are properly maintained, they remain essentially dry and in equilibrium and, even though some of the materials are relatively soft, the brickwork can endure for centuries.

Get small space home decor ideas, celeb inspiration, DIY tips and more, straight to your inbox!

Brickwork damage warning signs

Brickwork forms a vital structural element of a home, so any failure can result in damage to the fabric of the building, or even its collapse.

Old walls can have been mistreated or neglected, inappropriate maintenance may have been carried out, or the walls might have been patched or had openings cut into them so could be storing up unseen problems.

What to look for:

- Crumbling (spalling) bricks

- Loose, cracked or missing pointing

- Water spilling onto brickwork from gutters

- Internal or external damp patches

- The use of inappropriate mortars, paints and sealants for maintenance work

- Cracks through the brickwork

- Walls that bulge

This brickwork has been repointed using modern cement mortar, causing the surface of the brick to blow apart and crumble, or 'spall'

Repairing damaged bricks

Bricks that have spalled tend to make the penetration of moisture more likely, look unsightly and may have structural implications for the wall. There are a number of options available to rectify the problem.

Action:

- Consult a good bricklayer accustomed to working with old buildings.

- Carefully cut out and turn the brick round to hide the decay.

- Make up the face of the damaged brick with a tinted lime mortar.

- Cut out and replace severely damaged bricks.

- Use replacement bricks that match as closely as possible in size, durability, colour and texture and should be laid in the same way. Exact replication is very difficult but there are a number of good suppliers producing new handmade bricks at reasonable prices.

- Leave new bricks and mortar to blend in naturally over time.

- Be cautious about the use of secondhand salvaged bricks – they may be underfired and unsuitable for external work, or can sometimes be damaged.

Fixing pointing

Mortar joints that need repointing allow water to settle on the exposed top ledges of the bricks and penetrate into the structure.

Action:

- Rake out loose, soft mortar using an old screwdriver to a depth of at least 10mm.

- Repoint with a suitable lime mortar.

- Repointing requires skill and patience – ensure the person doing the work has both.

- Trial a small area with repointing before undertaking a whole wall.

- Never use an angle grinder to remove pointing.

Areas that have been repointed with modern cement mortar, rather than traditional lime mortar, can trap moisture, resulting in dampness within the building’s structure.

Instead of the moisture escaping harmlessly through the mortar joints, it moves to the face of the brick. In cold weather, frost freezes the water and the brick’s surface blows apart and crumbles or ‘spalls’.

Consider whether removing the pointing is in the best interest of the building. If more damage to the brick face is likely, and the pointing is not causing damp or other problems, it may be best to leave well alone.

If in any doubt, seek advice from the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) or a conservation builder. If it is best to remove it, use a narrow plugging chisel and small lump hammer to remove hard cement pointing.

The production of bricks became more mechanised from the 19th century, so there are many brickwork homes from the Victorian era, often with decorative details

Removing efflorescence from bricks

White deposits, known as efflorescence, appear on brickwork when water containing dissolved salts is brought to the surface. Although unsightly, efflorescence is not usually harmful to brickwork.

- Identify why the brickwork is becoming wet and rectify the problem.

- Brush or vacuum off the efflorescence.

- Never use water to wash off salts as this will make the problem worse.

Cracked or bulging brickwork

If brickwork is cracked or distorted it is important to find out the cause. It is not necessarily a reason for alarm as many old buildings settle naturally over time and lime mortar allows for movement.

- Look for obvious causes, such as rotten timber lintels above doors and windows, new unsupported openings, leaking drains and tree root damage.

- Consult a structural engineer.

Brickwork was often decorative in the Victorian era, and arched windows were sometimes seen

Removing paint and cleaning brickwork

Cleaning brickwork may harm the face of the bricks and hasten decay. Where cleaning is necessary due to graffiti, a severe build up of dirt, or because an inappropriate paint finish is trapping moisture, consult a specialist and trial the suggested method on a small area first.

Abrasive techniques are likely to remove the protective fired surface of the brick. Chemical cleaning can work but may cause staining and care needs to be taken not to saturate the brickwork when washing off. Water-based methods may result in efflorescence or lead to moisture penetrating the wall

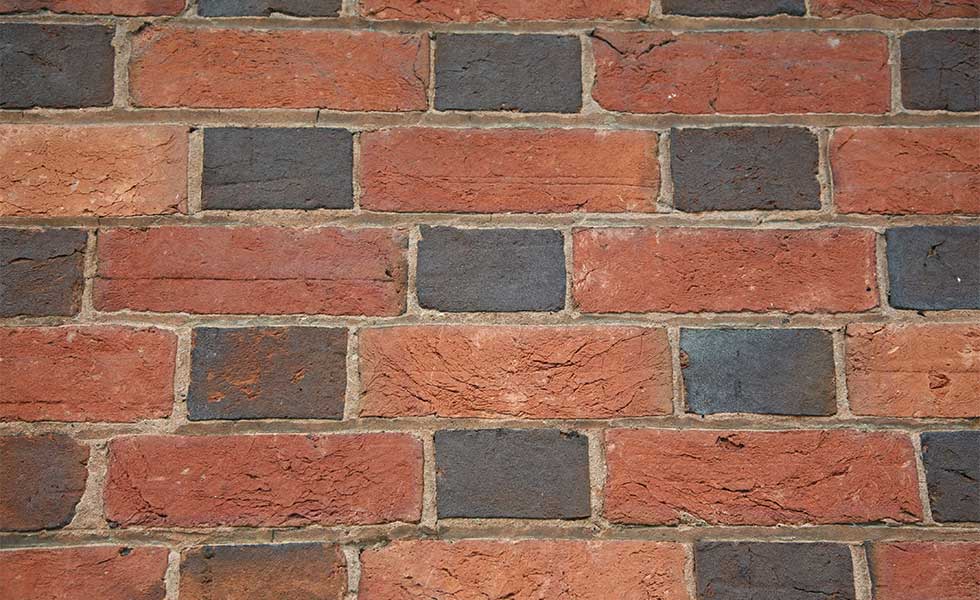

Styles of brickwork

The vast range of available brick colours and textures add character to a property. A high iron content turns bricks reddish when fired, while lime makes them white or yellow. These qualities, plus the regional nature of bricks, are reflected in their names – London stocks, Cambridge whites, Staffordshire blues, Accrington bloods and Leicester reds, are just a few.

Some decorative bricks are moulded or carved to provide detail or reliefs. Others, often above window and door openings, are ‘rubbed’ and ‘gauged’ so that they fit tightly together with only very thin mortar joints in between.

A technique called ‘tuck pointing’, popular between the late-17th and early-20th centuries, imitates fine gauged work by indenting the mortar with a thin line made of lime putty and silver sand to give the outward impression of a narrow joint.

Flemish bonding with alternating blue headers and red stretchers

A short history of bricks

Douglas Kent, technical and research director at the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings looks into the past of this ubiquitous building material

Bricks may be made from various materials, but are most commonly of clay, which normally contains a small amount of lime or iron oxide. Traditionally, they were made by hand in timber moulds.

Brickwork was constructed using lime or earth mortar; unlike modern cement products, this allowed the building fabric to ‘breathe’, which is important with old, solid walls to control dampness.

The pointing profile (finish of the mortar joints), bonding (arrangement of bricks) and brick size and colour have varied over time. These features can help, therefore, to date buildings.

Brickwork was little used in this country until the late Middle Ages. By Tudor times, however, it rivalled stone in popularity. Bricks tended to be irregular in shape and size, but the shapes could also be sophisticated, as seen in the twisted chimneys characteristic of this era. Walls were often decorated with diamond patterns of different coloured bricks (‘diaperwork’).

The more consistent shape and size of Georgian bricks reflects advances in manufacturing methods. Grey stock bricks and yellow London stocks were fashionable at the end of this period. Soft, rubbed bricks could be laid with very fine joints for high-quality work. A less expensive alternative was to create the illusion of thin joints using a technique called ‘tuck pointing’.

Brick production became mechanised from the 19th century and by the end of World War I, modern cement mortar, rather than lime, was widely employed for constructing brickwork.